Your Pitch Was Fine. Your Org Chart Was Wrong.

A former Google partnerships lead on what 10 years of vendor pitches taught her about how deals actually get signed.

Founders spend weeks polishing a pitch.

What they almost never see is what happens when they leave the room.

The side conversations.

The doubt.

The quiet “let’s park this.”

The Slack message that just says “thoughts?” with no follow-up.

Loretta lived in that room for ten years at Google evaluating vendor partnerships. She saw over 100 pitches. Maybe 10 survived. The other 90 probably still think the demo went well.

When I read her piece, it felt familiar. It maps onto the same patterns I keep coming back to here.

Can they repeat what you do.

Can they prove it.

What happens when it breaks.

And what happens after the meeting.

There’s a story in here about a vendor who bypassed the actual decision maker three times to reach someone more senior. It went about as well as you’d expect. Don’t skim that part.

I’ll hand it over to Loretta.

For years, I was the gatekeeper.

Startups would pitch me their SaaS tools, creative agencies, measurement platforms, all hoping to get access to Google’s app developer ecosystem. I decided whether they got to work with our customers or got politely archived.

Out of 100+ partnership pitches I reviewed, maybe 10 made it through. The gap between success and failure? It wasn’t the product. It was how they approached the sale.

If you’re trying to crack an enterprise deal with Google or similar corporations, here’s what actually works.

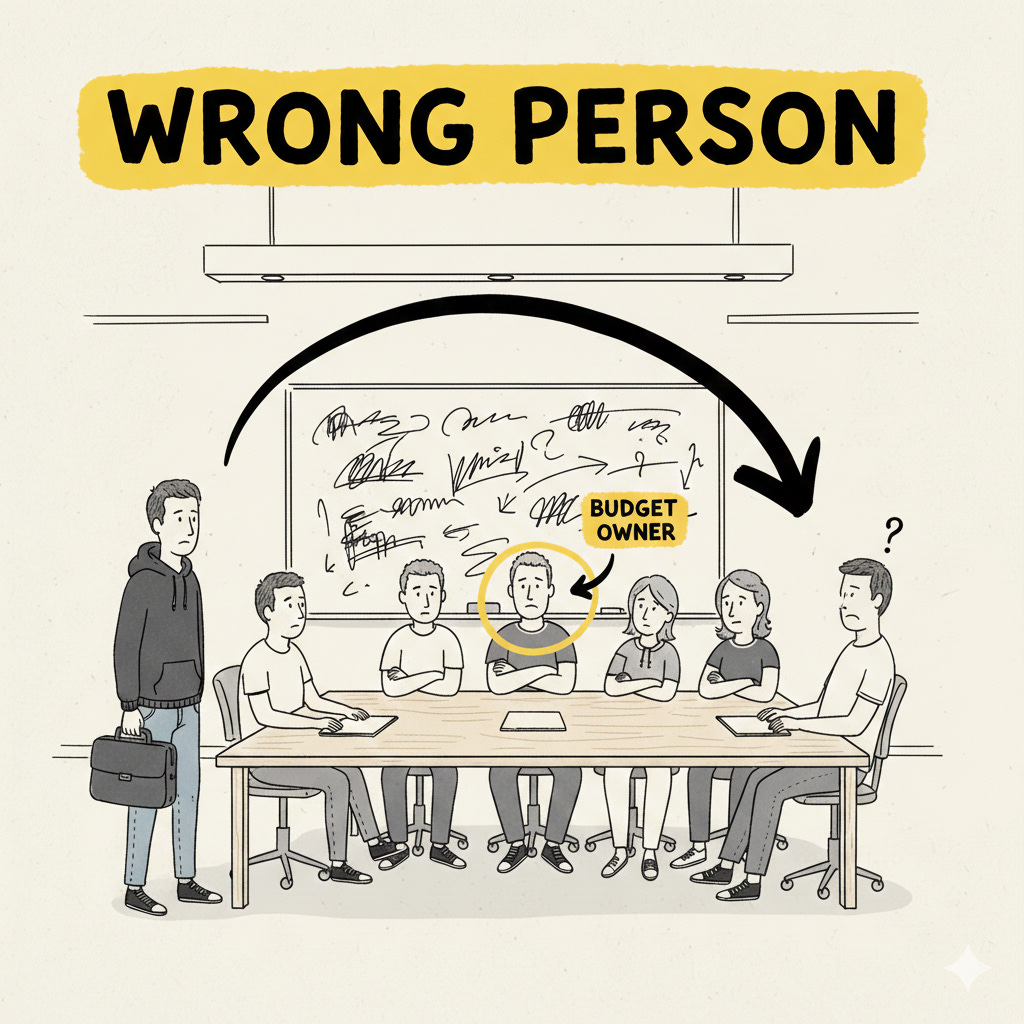

The org chart problem

One of the biggest challenges shared with me by my partners is how complex it is to navigate the organisation.

Unlike startups, where you have a very flat culture and people can easily connect you with the person in charge, at corporations like Google, it can be difficult to navigate, even internally.

To give a very simple example, at Google, there are entirely different organisations for Google Cloud, Google Play, YouTube, Google Ads, etc.; and within each organisation, they have their own sales, analysts, research, partnerships, marketing, and finance teams.

In my own role, I could easily have 100+ stakeholders just internally. Instead of talking to whoever is working in the company and hoping that they can connect you with a person who could help, what you need to do is really map your product into the organisation and see which teams or departments are going to be your best allies.

Easier said than done.

Here are some quick tips:

Read the company’s statement to understand their OpEx and organisational structure

Research whom your competitors interact with through press releases, LinkedIn updates, etc.

Check with your industry connections to see if they can share insights

Your goal is to gather enough information about the organisation and how it’s structured, so that you can identify which teams are most interested in your products. Reach out to one team at a time, because with each interaction, the knowledge you have gained might actually influence your research afterwards.

Research LinkedIn to find people in certain positions or teams. Note their locations, identify the reporting line, and try to map out the org chart.

Review LinkedIn and job descriptions to gain more context about what each role does.

Finally, reach out and talk to people, a lot of them. See if they can help you paint the remaining picture.

Finding the real decision maker

After narrowing your target to the correct teams, the next step is to identify the decision makers. Note that it’s plural, because in a lot of situations, signing an enterprise deal requires several teams’ collaboration:

Users: who are actually going to use the product

Budget owner (POC): the person owning all these external deals, subscriptions, and partnerships

Budget approver: the person and team that advise on the budget of the team as a whole, controlling the budget cycle, and approving budget requests, etc.

In a very typical scenario, you will need to speak to all the parties above. Connect with the users on different occasions to gauge their demand for the product, and get an ally who can then help you make a case to the person-in-charge; who, hopefully, will be keen to collaborate, and help you fast-track the necessary administrative processes with the pocket owner.

A quick tip because a lot of people get this wrong: the decision maker is not always at headquarters.

I had a vendor bypass me repeatedly to reach my director in Americas, when I am actually the budget owner for global partnerships. After the third bypass, despite positive product feedback from our teams, we never signed.

If you can’t navigate our organisation respectfully during sales, how could you handle the partnership?

Understand who owns the decision, and work with them, not around them.

What the winning pitches did differently

Identifying the owners is not going to guarantee you the deal unless you have the right pitch, and nailing that is a lot more challenging than you might have imagined.

I’ve interacted with different vendors, and here’s how the ones that got the deals did it:

Start with questions: understand the team (users’) goals, challenges, and day-to-day, the tools (ie competitors) they use, and team size & organisation chart, etc.

Explain how the product could solve the users’ problems: how it could save their time, improve workflow, etc. You are only able to make concrete examples when you have learnt enough about your users

Resolve their concerns: even when a product is demonstrating proven value to the team, the POC often has some concerns about its credibility, or its experience in working with big corporations. This is essential for the partner to ease these concerns before they are asked: your existing relationships, if any, with the company; enterprise customer cases; experience working with their competitors (extremely important); whether you have international exposure (offices, teams, customers)

Put together a tailored trial for the users: very rarely can a corporation sign an enterprise deal without trying. Propose a trial, get help from the POC to share and communicate it to the power users. Host training sessions for power users to help them understand why your product is important. Monitor trial activity metrics and identify insights, reach out to the users so you can provide support, answer feedback, and gauge interest. Your goal is to prove how your product can deliver the value you promise, make a case, and have the users advocate for you.

Why timing kills more deals than product

Okay, let’s say you’ve nailed all of the above. It doesn’t mean that you can sign the deal right now. The thing is, every organisation or team has a very different finance cycle.

For my team, we determined the ultimate budgets for the broader team at the beginning of the year. That often meant we might not have a lot of leeway to make in-year adjustments. In your communication with the POC, understand the budget cycle. This can give you a lot of clarity regarding what budget they can give and when they can give it.

Ideally, you want to come in at the right timing so you can help the POC put together a budget request to the budget owner (such as the finance or sales operations teams) before the next annual budget cycle is approved.

However, if the conversation happens mid-year, you can explore whether you could start with a smaller deal by tapping into unused budget from the current year. This allows you to establish a footprint with the hope of expanding into a larger deal for the following year. This can be a good strategy because for most enterprises, renewing a deal requires significantly fewer layers of approval than approving an entirely new deal.

All these circumstances will then influence the product proposal which you put together for the POC and the subsequent decision and budget approval.

As you might have realised, the company POC needs to be your best friend because they’re the person that determines whether they want to go through the additional administrative processes for you, which often takes up extra time for them.

After the deal (or the rejection)

Let’s say you have done everything you can. Chances are either the company will happily sign the deal with you and bring you on board as their first enterprise partner, or there is a possibility that they like the product but not enough to actually pay for the services right now. So, what do you do next?

If you have signed the deal, maintain regular contact with the POC, even if the relationship is officially passed over to the account management team. The POC is very likely to provide updates, such as changes in team structure, layoffs, etc., which you want to be the first to know so that you have extra time to prepare for the next renewal cycle.

Also, if your product has helped the POC successfully prove their work, reach out to them and see if they can connect you with other users in the company. An internal advocate with a pre-existing deal makes it much easier to expand your product subscription to new teams or departments.

However, if your POC is not able to sign the deal with you right now, ask questions to understand the real reason behind it. Is it because of current budget constraints, product limitations, lack of enterprise customer endorsement, or is it just not the right team? Continue to warm the lead and wait for a time when they might be able to convert. Meanwhile, continue to explore other teams that could be a better fit given the new information you’ve obtained about this company.

If the issue is about the budget cycle, help identify the right time to re-engage so you can ensure they put you in the first request. The goal is to continue cultivating relationships with enterprises through different touchpoints. You need to ensure your product remains top of mind, while slowly helping them develop the required trust before they are finally ready to onboard.

Enterprise sales is hard.

For each company, you’re dealing with 10+ stakeholders, 6-12 month cycles, and layers of bureaucracy. Most vendors give up because they underestimate the time investment or overestimate their product’s appeal.

But here’s what I learned watching the ones who succeeded: they treated it like a partnership from day one. They genuinely helped our teams solve problems, respected our processes, and played the long game.

The companies that cracked Google weren’t necessarily the ones with the best product. They were the ones who built trust, understood our constraints, and made our lives easier.

About Loretta

I spent a decade at Google working across digital marketing, strategic partnerships, and app development with thousands of companies worldwide. I helped thousands of companies globally from scrappy startups to Fortune 500s grow their businesses, and I am a passionate mentor at Google for Startups, Techstars etc.

Now I help bootstrap founders and marketers cut through the noise with practical, proven strategies through my newsletterMarketing Proven. I also offer mentorship sessions for founders growing their businesses, navigating enterprise sales, or simply workers struggling with their careers.

Fantastic article worth reading closely